Outraged Over American Complicity in Gaza Genocide, Philadelphia’s Young Arab and Muslim Voters Are Ambivalent This Election

Lauren Abunassar

As Election Day draws near, morality is at the top of mind for many young Arab and Muslim Philadelphians who are eligible to vote for the first time this election. Candidates’ proposed policies on Palestine and Israel — including their commitment to continued U.S. military aid to Israel in the midst of an ongoing genocide — are being used as a litmus test. In the final days of their battle for the White House, both Trump and Harris are rallying heavily in Pennsylvania, a crucial swing state this election. Harris will end her campaign in Philadelphia while Trump will head to Reading and Pittsburgh. If you ask young voters how they’re facing the prospect of voting, many will tell you they’re anxious, disillusioned, and ambivalent. What does one do when their vote holds power, but their voice has been ignored?

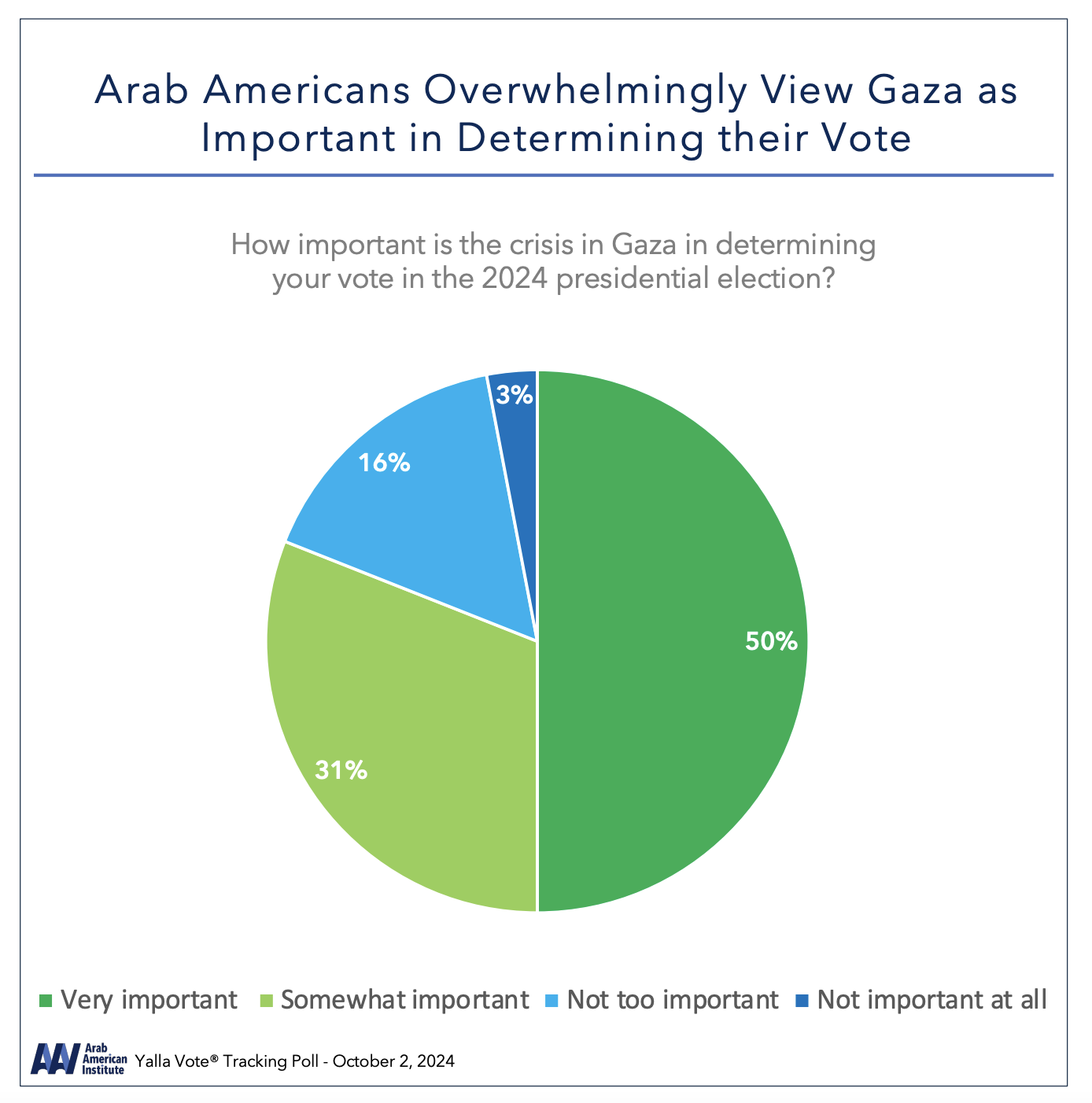

Last month, the Arab American Institute (AAI), a D.C.-based nonprofit dedicated to cultivating Arab American civic engagement, released a Yalla Vote tracking poll of Arab American voters, saying, “in our thirty years of polling Arab American voters, we have not witnessed anything like the role that the war on Gaza is having on voter behavior.” According to the AAI, Arab American voter turnout has consistently been in the 80% range. This year, however, that rate has fallen to 63%. Beyond this, only 55% of 18–29-year-old Arab Americans reported feeling enthusiastic.

Although Arab Americans have traditionally identified as Democrats, they now identify as Republicans or Democrats at the same rate of 38%, according to a poll conducted by AAI. Harris and Trump are tied with Arab American voters at 42% and 41% respectively, the poll showed. Image courtesy of AAI.

For 20-year-old Palestinian American Naheda Dahleh, a student at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, the ongoing genocide in Gaza is precisely why the sanctity of human life should be at the forefront of voters’ minds, even if it does make them single-issue voters. For many young Arab American voters, not to mention the countless allies within the pro-Palestinian liberation camp, no single issue demands more urgency and consideration than genocide.

“We don’t even know how many lives have been lost in Gaza. And even here in America, both Trump and Kamala want to increase policing. They want to build a border wall. There are all of these deadly policies, so it’s not about choosing the lesser of two evils when they are both evil,” Dahleh told Al-Bustan News.

The Arab American Institute’s Yalla Vote poll indicated that Arab Americans overwhelmingly view Gaza as an important issue in determining their vote. Image courtesy of AAI.

Though she plans on casting her vote for the Party for Socialism and Liberation’s presidential candidate, Claudia De la Cruz, she holds no illusions that De la Cruz will win. Instead, she believes if you can’t organize within the system, you have to organize outside of it. And this outside-the-system approach seems to her like the only place where moral decision-making is prioritized.

“The reality is, a lot of the rights that people campaign so hard for are just used as bargaining tools. That’s where the confusion comes from,” Dahleh said. The result is resounding disillusionment, and even disinterest in going to the polls. Dahleh said many of her peers are either considering only voting for local candidates or not voting at all. “You start to realize these politicians don't listen to and don't care about [Arab Americans],” Dahleh said.

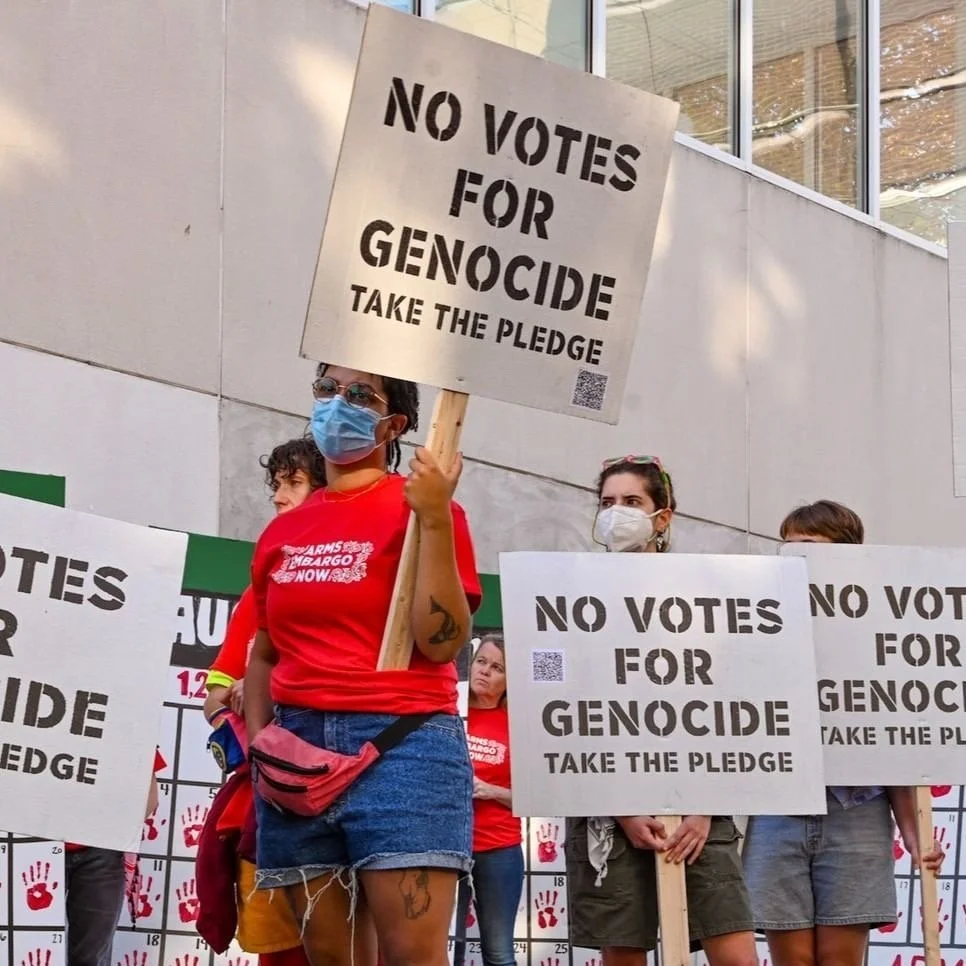

Dahleh grew up in Philadelphia and has been organizing actions for Palestine since she was 16. On Saturday, she helped plan a No Vote for Genocide rally at City Hall, which was organized as part of the Shut it Down for Palestine Coalition, the Answer Coalition and the Party for Socialism and Liberation. Though she recalls once feeling enthusiastic at the prospect of being able to vote for the first time, she said that today she is utterly exhausted by the moral apathy that rules the political ruling class.

“We don’t have to live like this,” she said. “We don’t have to be living just to survive.”

In addition to reporting a lack of enthusiasm amongst voters and an expectation of reduced voter turnout among Arab Americans, the AAI Yalla Vote tracking poll also showed that while 81% of Arab Americans view Gaza as important in deciding how they will vote, 54% said they would be more likely to support Harris if she were to demand an immediate ceasefire. Ultimately, the poll shows that Harris could recover some portion of the Arab American and youth vote: 60% of 18–29-year-old Arab Americans and 73% of Arab American Muslims say that they would be more likely to support Harris if she suspended arms shipments to Israel. But Harris suspending arms shipments to Israel is unlikely. In the face of this unlikelihood, voters’ enthusiasm about voting has waned.

An ally in the struggle for Palestinian liberation, University of Pennsylvania student, 21-year-old Muslim Bangladeshi-American Sabirah Mahmud finds herself torn over how to vote in the U.S. elections.

Like Dahleh, University of Pennsylvania student, 21-year-old Muslim Bangladeshi American Sabirah Mahmud told Al-Bustan News she finds herself similarly torn. Should she vote for, arguably, the most pro-Palestine presidential candidate Jill Stein of the Green Party? Or is her most moral option to not vote altogether?

“There is skepticism and confusion because Stein won’t ever win. There is the sense that no candidate is good, and that Trump will ruin this country,” Mahmud said. This is the first presidential election in which she is eligible to vote and she admits she lacks any feeling of ceremony or power at the prospect of casting her ballot.

“It makes me feel like [I’m] walking in a circle. And no matter where [I] go, there is no option. And in my head, the only morally safe option is just don’t vote at all, because we’re f—d either way,” Mahmud said.

It’s a surprising confession from someone like Mahmud, who grew up on the borders of various political arenas. She watched her mom work the Philadelphia election polls. In 2020, Mahmud was a surrogate on the Bernie Sanders campaign. She even discovered an image of herself attending a 2019 rally, while she was still campaigning for Bernie, was being used on a 2020 graphic launching Biden’s campaign, a move she believes is just typical of how electoral politics manipulates people of color. Mahmud is cognizant of the fact that every academic milestone in her life has coincided with a historic election: she was graduating eighth grade when Trump was elected, a senior in high school when Biden was elected, and now, she’s a year from graduating college. As a first-generation college student, Mahmud is accustomed to serving as the person everyone in her family comes to for voting advice. In 2020, she encouraged them to vote for Biden. Now, she doesn’t know if she should tell them to vote for Jill Stein or to just not vote at all.

“We can’t just put fear in people and say, ‘Well Trump is bad, so we have to vote for Kamala,’” Mahmud told Al-Bustan News. “In my eyes, I see no differences [between Republicans and Democrats]... Nothing has really changed these last four years. Gun violence has still taken the lives of multiple family members in Philadelphia. I experienced food insecurity under Obama and I was still food insecure under Trump. The same threats are so rampant… This election, I want to see low [voter turnout]. I don’t want to see votes for Kamala or Trump. And that’s what I tell my family.”

On Oct 13, in advance of the election, Philadelphians held a No Ceasefire, No Vote rally outside Philadelphia Democratic Party headquarters. Photo credit: Joe Piette

Mahmud, who hopes to work in human rights one day, recently returned to the U.S. after spending the past year and a half working with Syrian migrants in Jordan and Lebanon. The University of Pennsylvania evacuated her from Lebanon two months ago when Israel launched airstrikes on the region. The attacks on Lebanon have been deadly; on September 21 alone, Israel carried out a total of 111 airstrikes in one hour, as reported by CNN. Returning to the U.S. from such turmoil only to contend with rampant political ads, canvassers, and pollsters was a shock to Mahmud’s system. Even the man who recently approached her on the Penn campus to try and register her to vote unsettled her. “It bothers me how people are acting as though this is life or death. But life or death is already happening in Gaza and Lebanon. You’re scared because your rights are coming under fire?”

Another Philadelphia student, a University of Pennsylvania freshman who wishes to be identified with only the initial P., expressed a similar feeling of moral outrage.

This is also P.’s first election and he is planning on casting his vote for Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein. Though he knows she will not win, it’s a vote that feels both indicative of his desire for change and a reinforcement of what matters most to him this election.

“I align with the moral identity of the third-party vote because I appreciate how it seems nothing is set in stone,” P. told Al-Bustan News. “Nothing is set on precedent. Decisions are made based on what seems morally correct. Morally just.”

A Palestinian American, P. finds himself surrounded by friends who’ve been transformed into single-issue voters as a result of the genocide in Gaza. Many of them, he said, will not vote at all as a result: “They don’t want to contribute to the success of Trump or Kamala.”

Maya Mehta, a 20-year-old student of Pakistani and Indian descent, attending Bryn Mawr College just outside Philadelphia, and an organizer for her school’s chapter of Students for Justice in Palestine,

Maya Mehta, a 20-year-old student of Pakistani and Indian descent attending Bryn Mawr College just outside Philadelphia, and an organizer for her school’s chapter of Students for Justice in Palestine, is similarly surrounded by the question of whether or not abstaining from voting is the most tenable route to safeguarding her own moral compass. “In Philly and in bigger liberal cities, you see this derision from liberals asking ‘Don’t you know what will happen if you don’t vote for Kamala?’ My response is: ‘We do know what happens,’” Mehta told Al-Bustan. “But I hate people saying that because [the genocide in Gaza] is not an ‘issue.’ It’s the perpetuation of colonialism and imperialism. And it’s this entire thing of ‘if I don’t vote, or if I vote without taking into account the support of genocide, what else would I ever vote for?’”

Mehta describes her college campus as a restlessly political place. Mehta is from California and she and many of her classmates from non-swing states have even changed their registrations so that they can cast what feels like a more meaningful ballot. Still, there are times she admits to questioning the virtue of living in a state where her vote matters so much. “It’s moments like these where I wish that I went to UC Berkeley where I knew that my vote, or even abstaining from voting, wouldn’t matter,” Mehta said.

She is a political science major who consumes politics every day. And yet, there’s this desire to feel insignificant because the long-held sense of civic responsibility she feels about voting is in direct conflict with the moral responsibility she feels to Gazans.

It’s a confusing time, Mehta explains, because Harris is the objectively better candidate. And beyond that, she explains that many people of color at Bryn Mawr College see themselves in Harris, a Black and South Asian woman.

“We’re at school being taught to have agency. We’re in classes with only women. And then you see this woman running for president and it’s literally the quantification of all these things we’re being taught. But then there’s this single issue and you find yourself saying, for lack of a better word, ‘what the f—k?’”

Ultimately, Mehta said she is undecided about how she will ultimately vote.

The ambivalence about performing a civic duty that undergirds Mehta, Mahmud, Dahleh, and P.’s decision-making is simultaneously fed by a moral clarity they are unwilling to relinquish.

Philadelphia-based Marwan Kreidie, a candidate for Philadelphia City Commissioner, professor of political science at West Chester University and executive director of the Philadelphia Arab-American Development Corps, told Al-Bustan News of the ways in which this indecision is emblematic of the Arab American voting base as a whole — not just first-time voters.

Philadelphia-based Marwan Kreidie, a candidate for Philadelphia City Commissioner, a professor of political science at West Chester University and the executive director of the Philadelphia Arab-American Development Corps,

“I think, had the Democratic National Committee allowed a Palestinian speaker to speak at the Democratic National Convention, it would have gone a long way in alleviating concern. But you tell people Trump is going to be worse and they say, ‘There are 41,000 or 42,000 dead. How could it be worse?’” Kreidie said. These estimates are conservative, with other experts estimating the death toll to exceed 100,000—330,000, according to Euro-Med.

Kreidie sees Democrats at risk of losing Michigan. And in Pennsylvania, he said, the Arab American vote could influence the razor-thin margins between Trump and Harris. The takeaway is simple: “It would be great if Kamala would say something [to Arab Americans].”

In other words, while fear of a Trump presidency is real and great, Democrats cannot wager that Arab American voters will have the cognitive dissonance to cast a ballot for a party they see as apathetic to an ongoing genocide. They don’t have to move mountains to win back Arab American votes. But they need to, at the very least, acknowledge the reality of pain and suffering Arab Americans, and particularly Palestinian and Lebanese Americans, are experiencing.

“I would say I’m less hopeless, more pessimistic,” Mahmud said. “I don’t think there is any hope to be had. That’s my level of pessimism.”

To describe how she’s processing candidates’ appetite for the youth vote this election, she can’t resist bringing up the reality dating show Love Island.

“It’s insane how much the country is trying to [reach] Gen Z,” Sabirah said. “I was watching Kordell and Serena’s [Love Island USA’s season six winners] TikToks and they’d collaborated with Lyft to talk about discounted rides to the polls. I’m thinking literally anyone can use that discount and just go anywhere; they can’t tell if they’re going to the polls. And it’s Kordell and Serena… They were on a dating show about how sexy they were. [Politics] is not relevant to them.” It’s frustrating to Mahmud not because she’s mad at Kordell and Serena. But she is mad at the social pressure to vote for candidates that people do not actually believe in.

At the same time, even the prospect of not voting is not symptomatic of disengagement so much as moral dedication. Mahmud pinpoints Gen Z as “the most politically motivated generation of our time.” Politics, she says, is not something they could have ever avoided. In fact, Mahmud’s entire high school went on strike in support of gun control legislation in 2018, joining the national March for our Lives movement. At just 16, Mahmud founded Philly Climate Strike — now Philly Earth Alliance — and went on to work nationally for the U.S. Youth Climate Strike and Youth Climate Action Team. Political engagement, even when confusing, even when devastating, comes naturally to and feels essential for Mahmud and her peers. Everyone she knows who plans to vote is waiting for Election Day to make the daunting decision for whom to cast their ballots.

Election Day is an especially grim prospect for 20-year-old Palestinian American and Penn State junior Farah Latefa.

AAI’s Yalla Vote poll indicated that Arab Americans view the crisis in Gaza as THE most important issue in determining their vote, next to jobs and the economy. Image courtesy of AAI.

Latefa, whose parents are both from Gaza, visited her homeland for the first time in 2011. She is cognizant of the fact that she may never get to see Gaza again. Since Israel’s most recent bombardment of Gaza following October 7, she has lost her grandmother, several cousins, and many more. She started a GoFundMe to help remaining members of her family, including an aunt and uncle who are struggling with serious illnesses, and their four children—ages 18, 13, 8, and 4— all of whom are struggling with starvation. Before this, during her own trip in 2011, she herself survived several bombings. She thinks about those attacks when she faces an onslaught of campaign messages about protecting democracy and Americans’ rights.

Every day, it seems, Latefa sees her family name on a social media list of martyred Gazans. She incessantly watches videos of her people being killed and is simultaneously inundated with coverage of two candidates who continue to justify the mass casualties.

And though she has not yet decided how she will vote on Election Day she’s resigned to the fact that she cannot stand behind any candidate completely.

“In a way, whoever I vote for is killing my people… We want to protect democracy, but at what cost?” Latefa said. It’s impossible for her to separate the ongoing genocide in Gaza from her voting considerations. “It’s not easy to move around the fact that we are seeing our own people slaughtered and then we have the added pressure of voices saying ‘you have to vote because if you don’t, this person will do this and then this person will do that’ … We don’t even have time to grieve,” Latefa said.

She is keenly aware of the fact that casting her first presidential vote should be an exciting and empowering time. But as an Arab American who feels completely discarded by the electoral system, it’s more so a reminder to voters like Latefa of all that has been lost.

“Gaza was beautiful. We had everything there that we have in the Western world: shops, malls. We were human beings. We had lives. We had dreams,” she said. “My cousins who were killed followed the same path I’m following in terms of education, wanting to go to college, even liking the same soccer teams.”

“For something so beautiful to get so destroyed because of racism and propaganda is one of the world’s biggest losses,” Latefa said. “Gaza is the world’s biggest loss.”

***

NOTE: This story was produced as part of the 2024 Elections Reporting Grant Program, organized by the Center for Community Media and funded by the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation, and the Tow Foundation.

Lauren Abunassar is a Palestinian American writer and journalist. A Media Fellow at Al-Bustan News, she holds an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and an MA in journalism from NYU. Her first book Coriolis was published as winner of the 2023 Etel Adnan Poetry Prize.