From Tunis to Trenton: Alia Bensliman Keeps Her Amazigh Heritage Alive Through Her Art

Nisa Qazi

For Trenton-based artist Alia Bensliman, putting women at the center of her work is a responsibility she inherited from her late grandmother, the prominent Tunisian feminist Asma Belkhodja. Belkhodja served as the first Secretary General of the Union of Tunisian Women when the nation gained independence from France in 1956, and she was a singular and formative influence on her young granddaughter. “Because of my family,” Bensliman told Al-Bustan in an interview, “I grew up with the vocabulary of women’s rights.”

This vocabulary can be seen in Bensliman’s artwork, which often features feminist themes. From January through April of this year, her portraits of Amazigh women were exhibited at Princeton University Art Museum as part of a joint show, Reciting Women: Alia Bensliman & Khalilah Sabree.

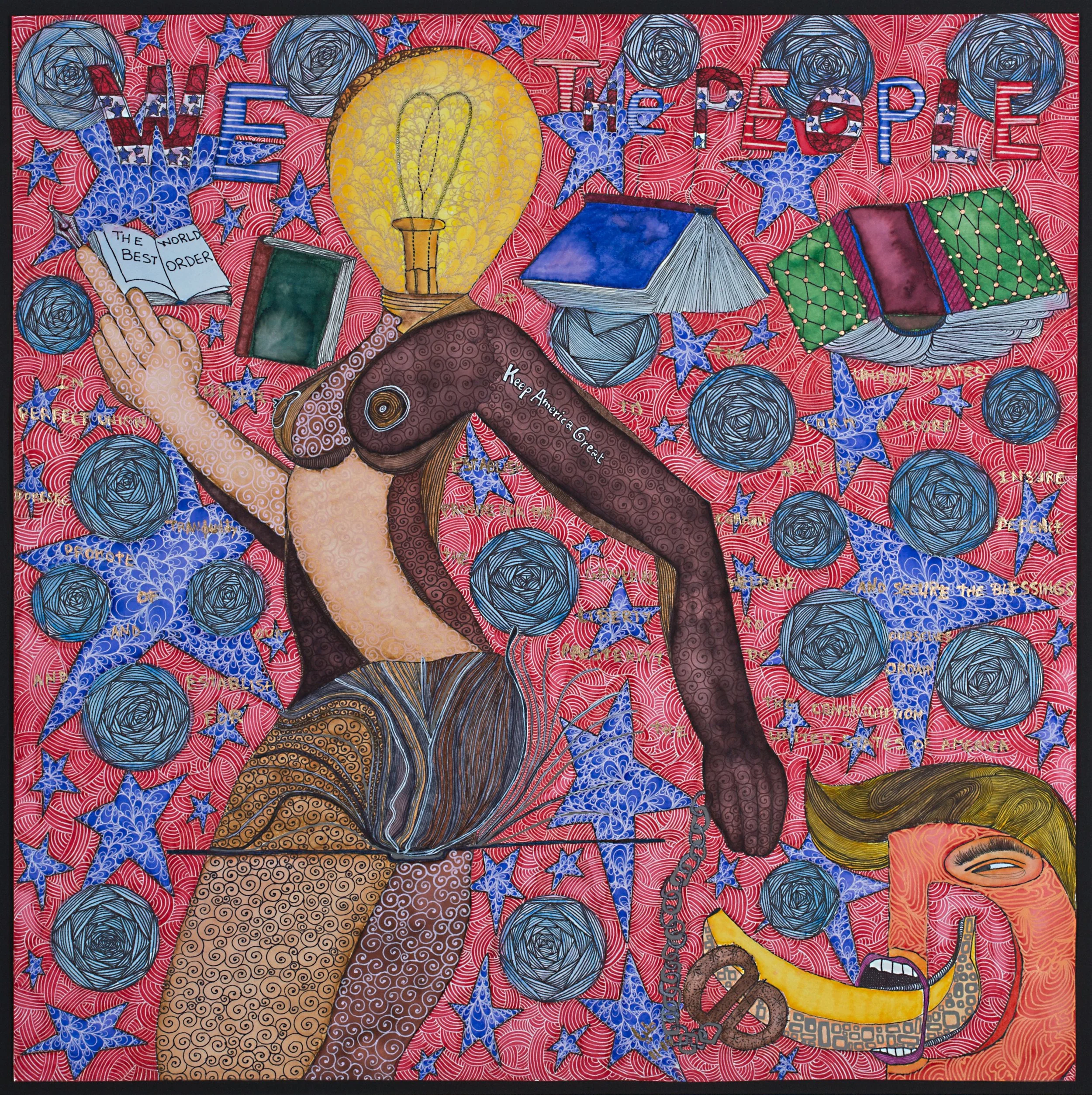

“Glorious Nights” (2022) is one among a series of portraits of indigenous Amazigh women created by artist Alia Bensliman. It was recently exhibited at the Princeton University Art Museum. Image courtesy of Bensliman.

These mixed media works, which incorporate Bensliman’s homemade watercolor paints, gold leaf, acrylic markers, charcoal pencils and ink, showcase Amazigh women’s distinctive tattoos, jewelry and traditional dress. The Amazigh (pronounced ‘ah-muh-zikh’) are the Indigenous people of North Africa’s Maghreb region and are widely referred to as Berber, though the term is increasingly viewed as pejorative.

The inspiration for the series came to Bensliman during the COVID-19 pandemic, when travel restrictions made visiting home impossible. As a way to quell her homesickness, she delved into her family’s Amazigh lineage, which she traces to her father’s ancestral village of El Guettar. She was especially interested in Amazigh tattoos. “When Amazigh women get married, they don’t get jewelry—they get tattoos. The groom brings the best tattoo artist in the area to the wedding ceremony,” said Bensliman, who spent several years studying Amazigh symbols both for their beauty and their historical significance, a fascination that dates back to her childhood exploration of Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Tunisian-American artist Alia Bensliman lives in Trenton and traces her family’s Amazigh lineage to her father’s ancestral village of El Guettar, Tunisia. Photo courtesy of Bensliman.

On the inside of Bensliman's forearm, she sports her own tattoo—an assemblage of traditional Amazigh symbols in black. A series of crisscrossed lines, representing a palm leaf, symbolize her marriage. Below it, a circle surrounded by dots represents a moon and stars: a mother and her children. Flanking that are two small plus signs, representing flies, which ward off the evil eye. “The more tattoos an Amazigh woman has, the more stories her body tells and the higher her rank in the family,” said Bensliman.

There are an estimated 30 million Amazigh worldwide, of whom 20 million live in Morocco and one million in Tunisia, where they have been economically and culturally marginalized by the state. “They have been forgotten—even by Tunisian people,” Bensliman said. She fears Amazigh culture will disappear altogether without concerted preservation efforts. “I want to bring back the culture and add it to the education program in Tunisia,” she said.

Bensliman cites Amazigh people’s sophisticated understanding of nature, and particularly natural medicine, as one of the traditional practices that all Tunisians should learn about. She believes that the Amazigh language, Tamazight, must also be taught. “They’re keeping the language alive in Morocco,” Bensliman said. “But in Tunisia, it is almost completely lost, replaced by Arabic. We say we are Arab, but we have been brainwashed. We are Tunisian. It’s not the same.”

After emigrating from Tunisia in 2009 at age 26, Bensliman settled in Trenton with her husband, a Tunisian American. She began volunteering as an educator at Artworks, a center for visual arts located in downtown Trenton. Bensliman’s loyalty to New Jersey’s capital has much to do with its thriving art scene, which she found to be a supportive and inspiring environment in which to adapt to life in the U.S. and grow as an artist.

While she hasn’t experienced any negative reactions when she identifies herself to locals as an Arab Muslim, she has noticed that it gives people pause and leads to follow-up questions. But telling Trentonians she’s from Africa? That always elicits the same response, Bensliman said: “Africa? We love you!”

Reactions to her work have been positive as well, with one notable exception. Bensliman remembers the feedback she received when she unveiled her 2016 painting “Grab’em by the D,” her response to the now-notorious Access Hollywood recording of then-presidential-candidate Donald Trump talking about his treatment of women.

“Grab’em by the D” (2016), pictured above, is Bensliman’s response to the Access Hollywood recording of U.S. President Donald Trump talking about his treatment of women. Image courtesy of Bensliman.

“Some people said they wanted to hug me, but others were very insulting towards me,” said Bensliman, adding that she was surprised that people were more upset about her painting than the comments that inspired it—a sign of society’s continued hostility toward women, despite the gains of women’s movements.

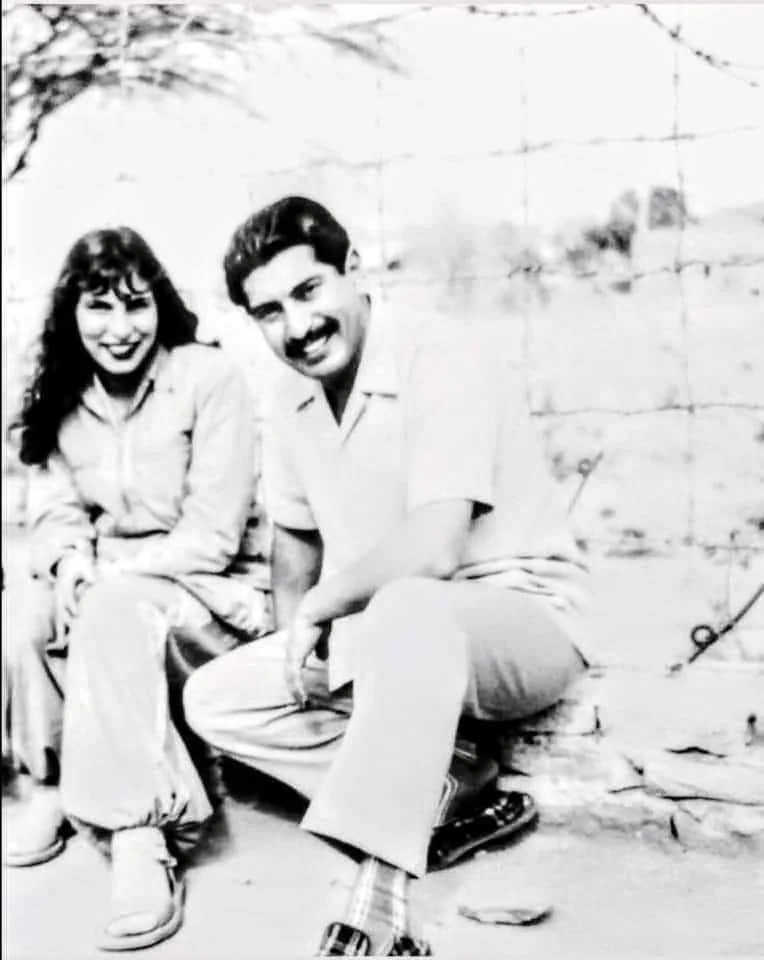

Pictured above are Alia Bensliman’s grandparents, Asma Belkhodja and Azouz Rebaï in Tunisia in 1954, before they married. Photo courtesy of Bensliman.

The theme of liberation—from patriarchy and from colonial exploitation—was also galvanizing for Bensliman’s grandmother. Coming of age in the final years before Tunisia’s independence, Belkhodja was drawn to movements pushing for progressive social reforms, including greater equity for women. She was a member of the Neo Destour party along with her husband, Azouz Rebaï, who served as Tunisia’s first post-independence Secretary of Youth and Culture, and Habib Bourguiba, a friend and political leader who became the first president of the newly independent nation. Throughout her life, Belkhodja advocated for women’s health and reproductive rights, the labor movement, and the rights of people with disabilities.

It was in this intellectual and political environment that Bensliman’s social consciousness—and rebellious streak—were formed. “I had kids’ books from UNICEF and from UNESCO, which talked about the rights of children,” she said. “Books about how children can change the world.” But learning disabilities made school a difficult and unhappy experience for Bensliman, so with her mother’s support, she decided to pursue fine arts and enrolled at École d’Art et de Décoration de Tunis. Following graduation, she worked as an art teacher for children with intellectual disabilities.

Today, Bensliman continues to work as an arts educator at Artworks, where she teaches adults and youth environmentally friendly approaches to artmaking. She also serves on the center’s Community Artist Board and volunteers wherever she is needed. “I'll be honest,” she said. “I'm living a dream right now. I have a dream job.” And although her homesickness persists—she noted that she is particularly nostalgic for the smell of the stone ruins at Carthage—she is determined to stay in Trenton. “It has so much potential,” she said. “So much to give.”

For her part, Bensliman is helping the city meet that potential by participating in her first public art project, a mural that will adorn one side of the New Jersey State Prison on Trenton’s Cass Street. Organized by Artworks, the project is a collaborative effort by a group of artists, slated to be unveiled by this fall. “I’m very excited to participate,” she said. “I hope it has a positive impact and brings pride to the community.”

***

A Media Fellow at Al-Bustan News, Nisa Qazi is a writer and editor based in Delaware County, PA.